if everything was, would anything be?

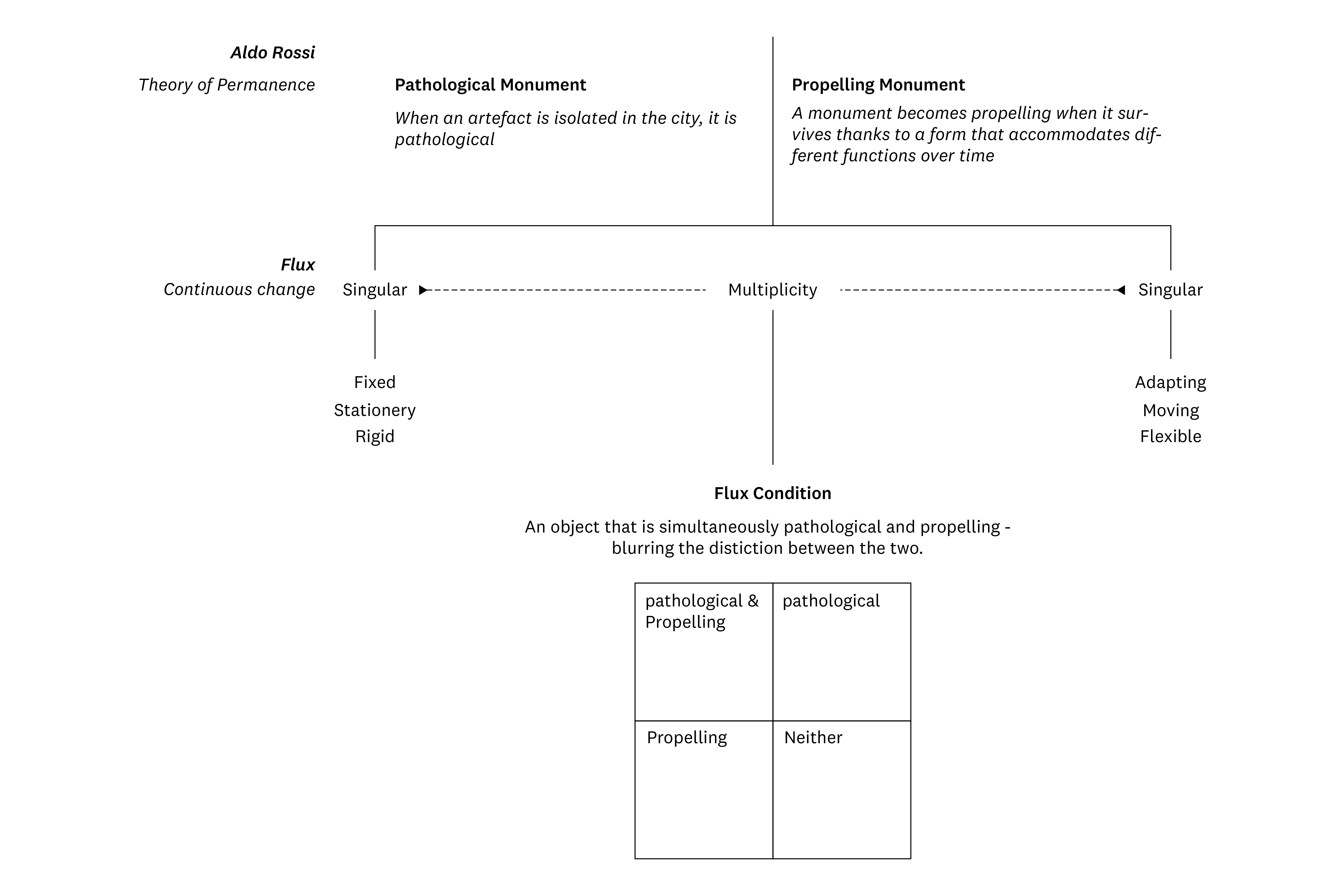

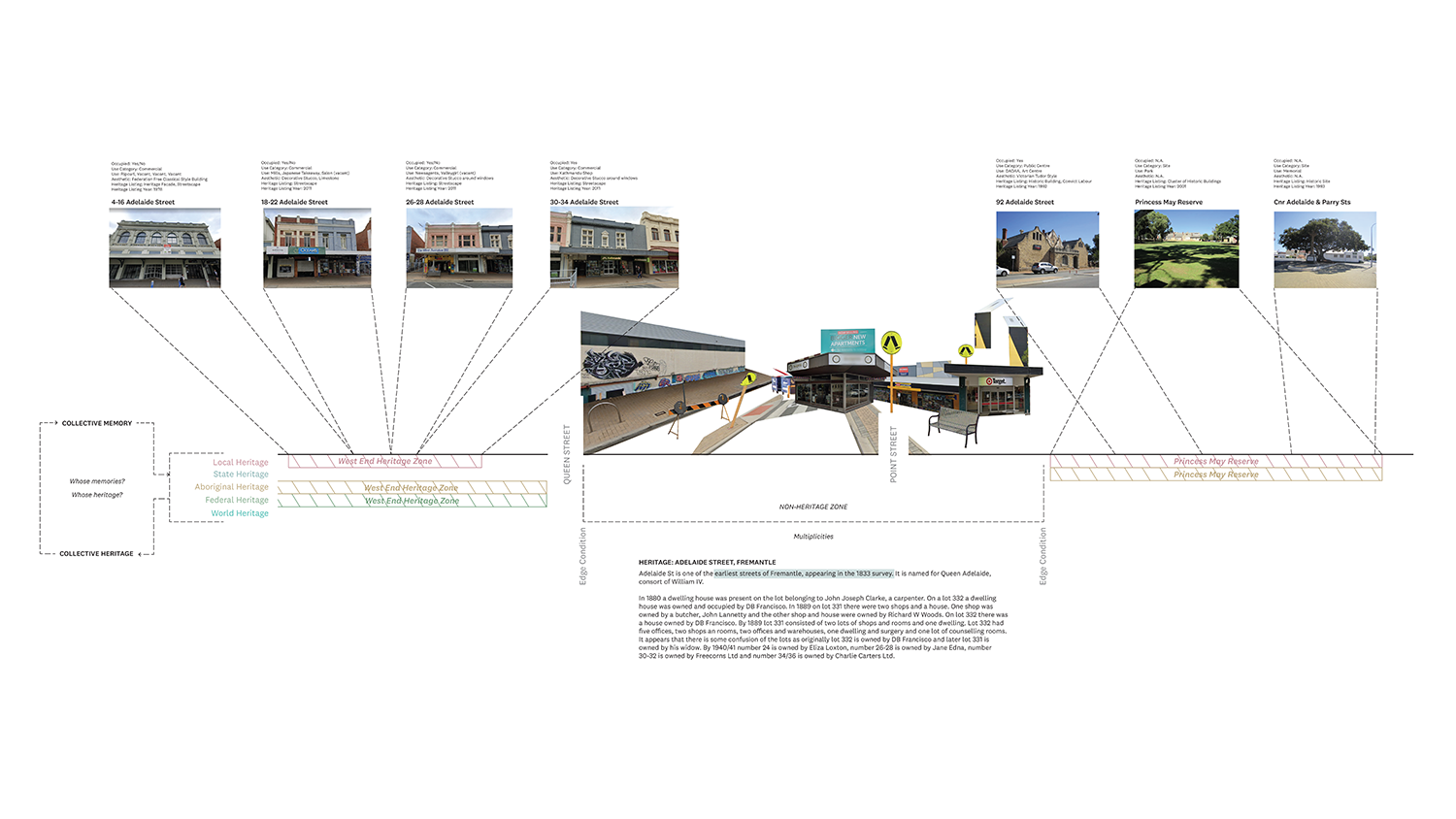

"If everything was, would anything be?” seeks to question the clear distinction and hierarchy between what is and is not heritage within the City of Fremantle. It aims to do this by blurring the identifiable heritage qualities by introducing material elements within the urban landscape. The project began by mapping the various heritage overlays within the city to identify what areas are important to what groups. Through mapping these heritage overlays, it was found that the Princess May Reserve was isolated within the heritage zoning of Fremantle. I then explored Adelaide St, the link between Fremantle’s West End heritage zone and the Princess May Reserve heritage zone. A matrix drawing was constructed to explore the various heritage overlays along Adelaide Street and the buildings that occupied those zones. Along with exploring the heritage zones, the non-heritage zone was also explored. This study revealed that the heritage zones look at the singular historical monument, while the non-heritage zones explore the multiplicities of place.

Mapping the (non)Heritage Zones

The project began by mapping Fremantle’s heritage overlays to understand what the city deems worthy of protection. This analysis revealed a clear hierarchy: heritage zones focus on singular monuments—individual buildings of architectural or historical significance—while non-heritage areas contain multiplicities of everyday materials and uses that form the fabric of daily life. The Princess May Reserve emerged as an isolated heritage zone, disconnected from the West End’s protected area. Adelaide Street, linking these two zones, became the site of investigation. By mapping what is and isn’t designated as heritage, the project questions why certain elements are preserved while others are ignored, challenging the assumption that heritage must be monumental rather than ordinary, singular rather than collective.

A New Heritage Material: A Multiplicity of Materials

Instead of focusing on a single heritage material—such as Fremantle’s iconic sandstone—varying materials are aggregated into heritage objects that subvert typical heritage conventions. These objects allow us to question what constitutes heritage and challenge our embedded notions about it. They rethink heritage as an act of care, embedded within our environment, and promote a ground-up approach to our collective memories.

A Series of ‘Temporary’ Pavilions

The proposal creates a series of pavilions on the site that can be disassembled. Each building is constructed from components that allow for future removal, reflecting the fluid nature of the heritage proposal. This approach is exemplified in the garden pavilion’s footings, which use rocks from local quarries. The frame is scribed to the rocks and simply rests on top. This version of Princess May Park exists in a state of flux, forming part of its ongoing history.